By Emily Dickson

Years of research indicates joint-related problems are the main reason for performance loss in horses. It is estimated that 60% of equine lameness is caused by degenerative joint disease, which includes osteoarthritis (OA)--the imbalance between cartilage synthesis and degradation.

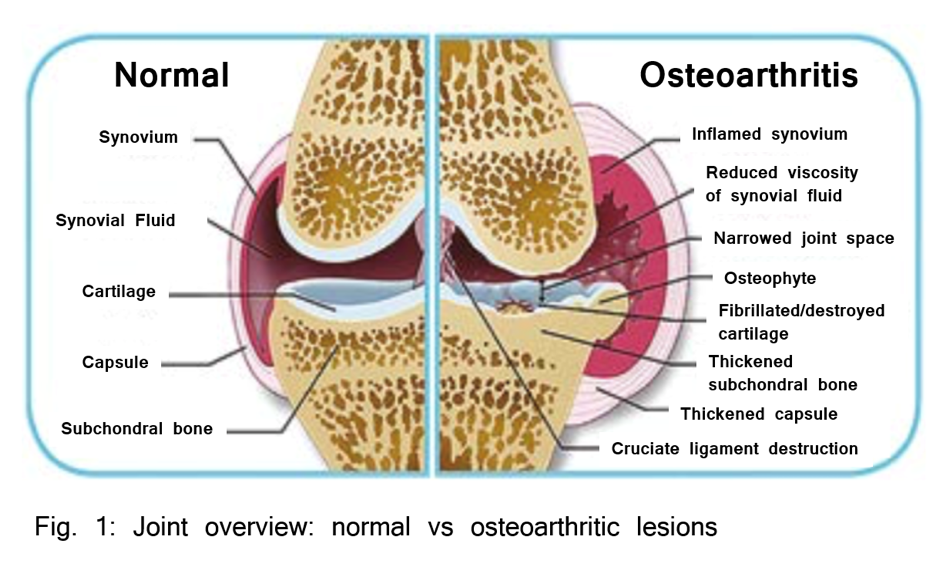

When we think about OA in horses or humans, most of us know that it ends in the breakdown of cartilage, resulting in painful, and sometimes debilitating, bone-to-bone contact within the joint.

What we may not consider is that cartilage is a living, dynamic tissue, containing biomarkers that we can measure to tell us more about what is going on in the joint. Now that’s exciting!

Before we get into the markers themselves, let’s make sure we’re on the same page with equine joint cartilage details and information.

Cartilage Anatomy 101

Cartilage covers the ends of bones in synovial joints, which is just a joint that allows for movement—the ones we typically think about, like our elbow or knee, or your horse’s carpus or hock.

Cartilage is composed of chondrocytes, the basic building block cells, and an extracellular matrix.

I think it can be helpful to think about cartilage as a city.

The chondrocytes are like construction workers. They’re responsible for regulating cartilage synthesis. The extracellular matrix (ECM) has two main components: type II collagen, which you can think of as the road system, and a proteoglycan network, which you can think of as buildings and houses.

The chondrocytes are always working, but the interesting thing about cartilage is that it is avascular, meaning there is not a lot of blood or nutrient flow. In other words, cartilage is like a small mountain town--resources coming in and going out are limited--therefore, the chondrocytes can only do so much at a time.

Collagen production is often thought of as a “once-in-a-lifetime” process, and while repair and turnover are possible, it does not happen quickly. You know how road construction goes…

Collagen turnover is actually estimated to take 120 years in dogs and 350 years in humans!

In contrast, the proteoglycan network is thought to be completely replaced after 300-1800 days. I’m sure you can relate to the fact that home and building repairs/remodels are much more manageable than completely replacing a system of roads.

The most well-known type of proteoglycan in cartilage is chondroitin-sulfate, but there are also others, like keratin sulfate.

In between the bones in the joint, in direct contact with cartilage, is synovial (or, joint) fluid. This acts as a shock absorber and lubrication, but also as the main communication mechanism between all the joint structures. It is the medium through which nutrients can be delivered to and waste removed from cartilage. Synovial fluid acts as the vehicles in our city, everyone and everything enters and exits through it.

Equine Cartilage Biomarkers

A biomarker is just an indicator. It is something we can measure to quantify a biological process in the body.

In people and horses, there are hundreds of biomarkers for all kinds of different things. In regards to cartilage, we are typically looking at biomarkers specific to type II collagen and proteoglycans: the two main components in cartilage.

Two biomarkers that are commonly researched are Carboxypropeptide of Type II Collagen (CPII) and Collagenase Cleavage Neoepitope of Type II Collagen (C2C).

Don’t get overwhelmed by the names (it's a lot, I know). Here’s what you need to know:

CPII is a measure of collagen synthesis and C2C is a measure of collagen degradation in cartilage.

We’ll get into more on each specific biomarker in upcoming blog posts.